LaToya Ruby Frazier

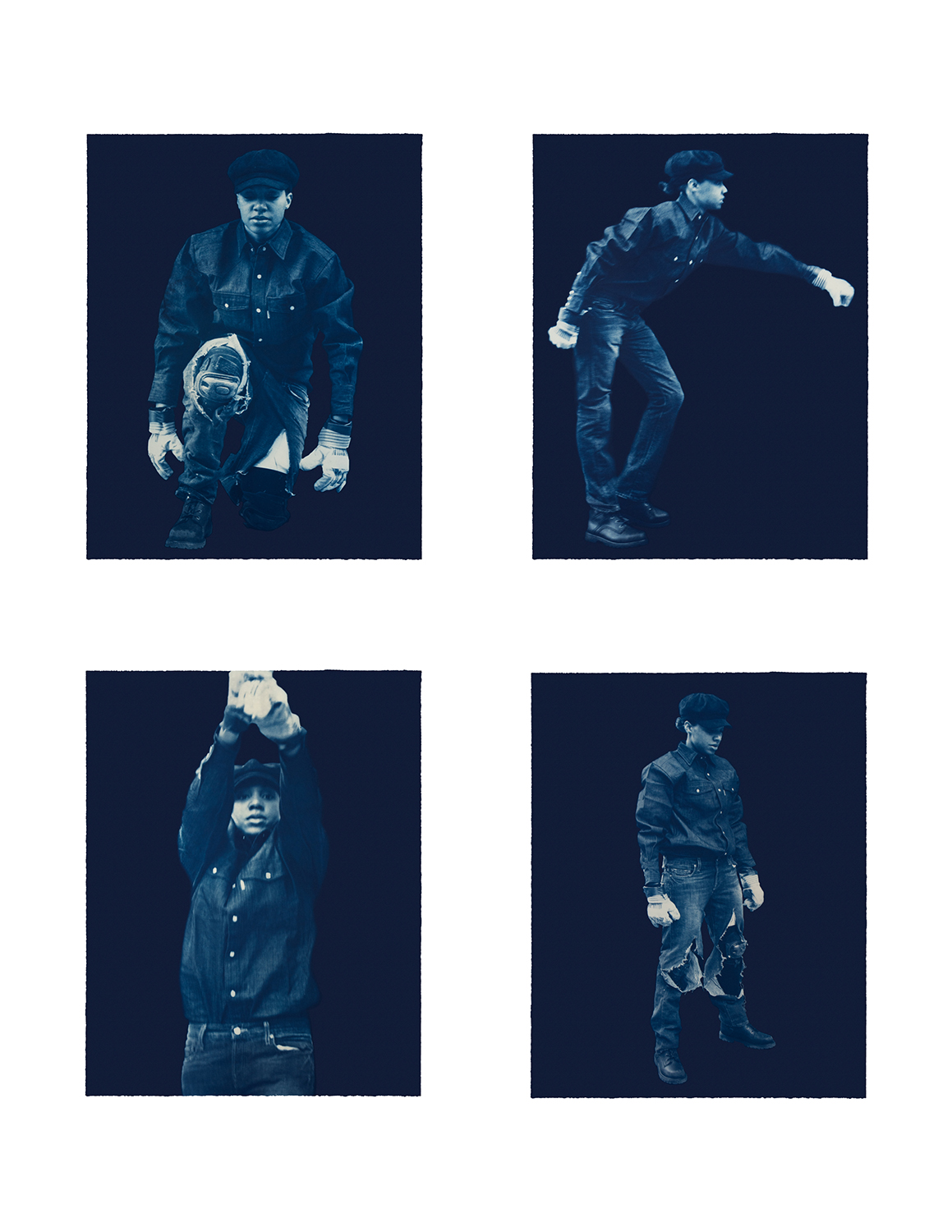

If Everybody’s Work Is Equally Important (I) and If Everybody’s Work Is Equally Important (II) by renowned artist LaToya Ruby Frazier were produced through the Printshop’s Publishing Residency Program in 2016.

Much of LaToya Ruby Frazier’s work focuses on her hometown of Braddock, Pennsylvania, and her family, which has been there for generations. In addition to the city’s role in the development of the U.S. steel industry—and, consequently, the country’s transition from industrial to post-industrial capitalism—her startling and disarming photographs of Braddock capture its history of segregation based on race and class, its extreme environmental toxicity, and the abandonment of its many sick citizens by the city’s only hospital, which closed in early 2010. Her images are grounded in a very specific sense of place, yet they speak to universal experiences of exploitation and injustice. Unlike the documentary photographs for which she’s best known, these two suites of cyanotypes, If Everybody’s Work Is Equally Important? (I and II), have a more abstract relationship to the situation in Braddock. By stripping away that specificity, she imbues the images with visceral force.

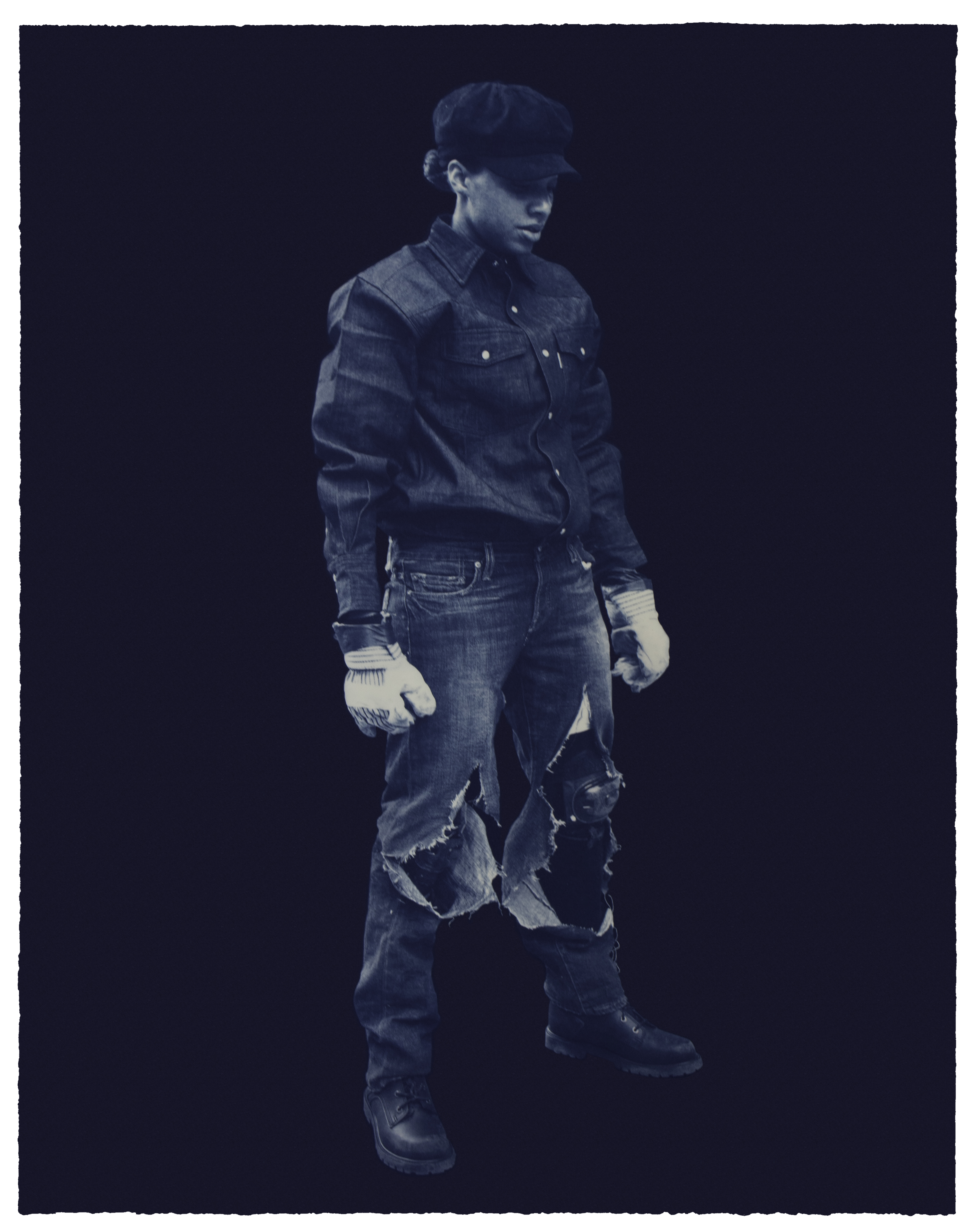

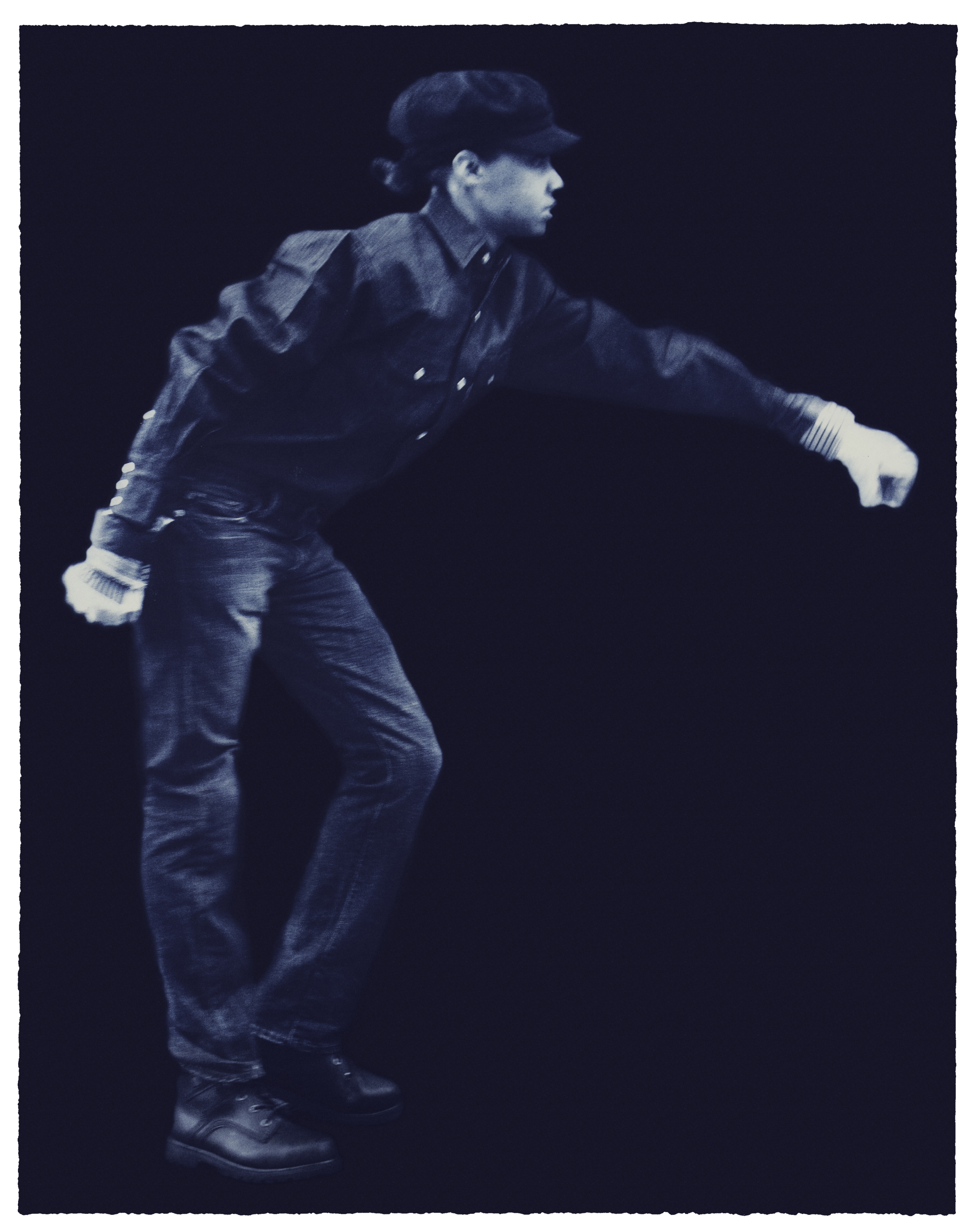

In December 2010, Frazier donned a crisp Levi’s denim shirt, pair of jeans and cap, and went to the brand’s pop-up store in New York’s SoHo neighborhood. On the sidewalk outside the shop, she performed a series of movements based on the typical actions of a Braddock steel mill worker, wearing her Levi’s uniform down to shreds in the process. The solitary, grueling performance was a stylized protest against Levi’s ad campaign “Go Forth,” which traded on the perceived grit and authenticity of her ruined hometown.

“In 2010, the advertising agency Wieden+Kennedy and Levi Strauss & Co. launched a global campaign, using my hometown as its backdrop, to promote the lifestyle and ideology of hipsters colonizing communities like Braddock, which have been abandoned by local governments,” she explains. “What this campaign omitted was the fact that Braddock is a 13-block-wide industrial town polluted by toxic industries on top of land mostly occupied by elderly, working-class, single-parent-household African-Americans. Under these circumstances, how can Braddock be a ‘new frontier?’ ”

The prints are based on photographs from Frazier’s Levi’s performance, all contextualizing details stripped away so she appears alone against a monochrome backdrop. The three prints in the first suite are close-ups highlighting the physicality of the performance and its toll on the artist’s garments, while the four prints in the second suite are full- and half-body portraits capturing specific poses and movements. The former have an almost forensic quality, isolating visible effects of the performance, while the latter possess a militant theatricality. Without the context of the steel industry, Braddock, Levi’s, and the shift from an economy based on industry to one based on images and information, the prints become records of an enigmatic and seemingly self-destructive ritual that underline the tragic prevalence of the problems Frazier has devoted her career to addressing.

“I see all the same symptoms and issues in all these countries and all these cities,” she has said. “Other people feel like they can confide in me things they’ve never said to anyone else, because it was hurting for so long and so painful—but they saw it in the photographs. That’s when art and photography transcend everything else.”

Frazier’s choice to frame her image in the deep, denim-like blue of the cyanotype, once the medium of choice for making architectural plans, satirizes the Levi’s campaign’s Rust Belt colonialism. These images suggest that the rhetoric of reconstruction and redevelopment is never purely altruistic, often seeking to erase difficult histories while displacing disempowered locals. The choice of medium also echoes the structural inequalities that Frazier finds manifested so devastatingly in Braddock, suggesting that design and construction can serve to build places up while keeping people down. By employing a medium once prevalent in architecture to offer her take on Levi’s’ insidious campaign, Frazier makes the connections between old and new modes of exploitation visible, giving us blueprints for resistance.

Excerpt from Editions ’17 by Benjamin Sutton

LaToya Ruby Frazier (b. 1982, lives and works in Chicago, IL) received her BFA from Edinboro University of Pennsylvania (2004) and her MFA from Syracuse University (2007). She also studied under the Whitney Museum of American Art Independent Study Program, and was the Guna S. Mundheim Fellow for visual arts at the American Academy in Berlin. Frazier works in photography, video and performance to build visual archives that address industrialism, rustbelt revitalization, environmental justice, healthcare inequity, family and communal history. In 2015 her first book The Notion of Family (Aperture 2014) received the International Center for Photography Infinity Award.

Frazier’s work is exhibited widely in the U.S. and internationally, with notable solo exhibitions at Brooklyn Museum; Seattle Art Museum; Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston; and Contemporary Arts Museum Houston. Her work has also been featured in the following group shows: The Generational Triennial: Younger Than Jesus (2009), New Museum, NY; Greater New York (2010), MoMA PS1, NY; the Whitney Museum of American Art Biennial (2012), NY; and 54th Venice Biennale among many others. Frazier is the recipient of many awards, including the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Award (2015), a fellowship from John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation (2014), Gwendolyn Knight & Jacob Lawrence Prize of the Seattle Art Museum (2013), the Theo Westenberger Award of the Creative Capital Foundation (2012), the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation Award (2011), and Art Matters (2010).

Her work can be found in public and private art collections such as Museum of Modern Art; Brooklyn Museum; Seattle Art Museum; Carnegie Museum, Pittsburgh; Library of Congress, Washington, DC; Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York among others.